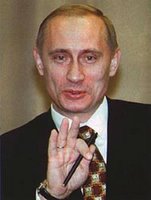

Who were the oligarchs? The question may seem premature, while Russia's economic élite still exerts disproportionate influence over Russian society. Moscow actually has more dollar billionaires than New York. However, a drastic change has occurred during the Putin presidency. Whereas Boris Yeltsin's second presidential term was dominated by the oligarchs, Putin has largely succeeded in breaking away from their influence. Thus, the heydays of Russian business oligarchy seem to have passed, turning oligarchs into mere tycoons.

Who were the oligarchs? The question may seem premature, while Russia's economic élite still exerts disproportionate influence over Russian society. Moscow actually has more dollar billionaires than New York. However, a drastic change has occurred during the Putin presidency. Whereas Boris Yeltsin's second presidential term was dominated by the oligarchs, Putin has largely succeeded in breaking away from their influence. Thus, the heydays of Russian business oligarchy seem to have passed, turning oligarchs into mere tycoons.As Vladimir Putin seized power in Russia in 1999-2000, it was much thanks to the support of a few influential Russian businessmen. Their relations to the Kremlin, and above all president Yeltsin, were so close that Russians referred to them as the "family" - signifying a merger between the Yeltsin clan and the major Russian business tycoons of the 1990s. At the time, the tycoons wielded such influence and power over Russia that the country stood on the verge of oligarchy.

In contrast to Yeltsin, Putin at an early stage signalled that things were about to change. Such signals were initially incomprehensible for most oligarchs, as they were used to easy access to the president. However, access was soon denied with Putin in power - much to the fault of the oligarchs themselves. People like Berezovsky and Gusinsky had major fallouts with Putin already in early 1999, much because they treated him as a puppet on a chain. Hopes that they could control the new and inexperienced president were soon lost.

Instead, Putin formalised relations with major business by channeling contacts through the

Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs and by regular and more official meetings with leading businessmen. The message that gradually evolved during Putin's first presidency was becoming increasingly clear: Hands off politics! As long as business did not meddle into politics, the oligarchs were to be left alone in generating profits. However, if business ventured into threatening state interests, there would be hell to pay. So, who were the winners and losers of this transition?

The losersThe first victim of Putin's new policy was Russia's "capo di tutti capi" -

Boris Berezovsky. His influence over Russia was so great by the end of the 1990s, that he was often called the "Grey Cardinal" of the Kremlin. With six major bank

owners, Berezovsky in 1996 formed the "Big Seven" who were instrumental for the reelection of Boris Yeltsin. Seeing himself as a "kingmaker" Berezovsky was rewarded by Yeltsin in becoming first deputy secretary of the National Security Council, then secretary of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). Winning a parliamentary seat in 1999, Berezovsky's luck started to turn. Having first brought Putin to power and then severely aggravated him, the methods of Berezovsky's business conquests - Aeroflot, Sibneft, aluminium industry, the ORT TV-channel etc - were turned against him. Only six months after the 1999 parliamentary elections, Berezovsky was forced to go into exile, on charges of fraud, money laundering and other financial crimes. After several demands for his extradition to Russia, Berezovsky was finally given political asylum in Great Britain.

Putin's second victim was media tycoon

Vladimir Gusinsky - Russia's equivalent to Rupert Murdoch. Through his holding company Media Most, Gusinsky had great influence over Russian media, not least through the TV-channel NTV and the newspaper Segodnya. NTV and Segodnya were long regarded the nucleus of

new independent media in Russia, even though it is obvious that Gusinsky at times used his media power for political purposes. The most flagrant example was the massive endorsement for Yeltin's reelection campaign in 1996. However, with Putin in power, Gusinsky's overinflated ego, a flamboyant lifestyle, and a propensity for unsound investment were factors that soon put him at loggerheads with the new master of the Kremlin. This all led to his eventual downfall. After a series of police raids and legal actions against himself and his companies, Gusinsky went into exile in Israel in 2001. In his absence, Gazprom and other companies seized the remainder of his business empire, and it its unlikely that the media tycoon will return to Russia, not least because legal authorities have long sought his extradition on fraud and embezzlement charges from several European countries.

The case that has perhaps been given most attention internationally is that of

Mikhail Khodorkovsky. Regarded as a banking genius, Khodorkovsky in 2003 was Russia's wealthiest man. Back in 1990, he formed the Menatep bank, which provided credit to state enterprises, and participated in dealing with privatisation vouchers, thus gaining

control of several large companies. He entered into chemical and textile industries, construction, mining and oil enterprises. In 1995, Khodorkovsky gained a controlling share of the oil giant Yukos, which soon became the jewel in the crown of his business empire. In the early 1990s, Khodorkovsky was known for his murky business deals in the privatisation of Russian economy. However, at the turn of the millenium he had transformed his public image to that of a protagonist of economic transparency, publicly crusading for stockholder and investor rights. Thus, Yukos was the first major Russian company to publish reliable quarterly reports. Still, economic influence was not enough for Khodorkovsky. He wanted political power as well. In supporting parties opposing Putin and the Kremlin, Khodorkovsky soon became the target of Kremlin's anti-oligarch crackdown. He not only posed a political threat. He also planned the construction of several strategic pipelines, which - if realised - would have given him a disproportionate influence over Russian business making him independent of political pressure. In addition to a political threat, Khodorkovsky thus also posed an economic threat to major interest groups within business and politics. It should therefore have come as little of a surprise when Khodorkovsky was arrested in October 2003. After a lengthy trial, displaying the Russian legal system as a travesty of justice, Khodorkovsky was sentenced to nine years imprisonment and his financial assets were gradually dismembered by his enemies within state and private business. At the time of his arrest, he was considered the most powerful of the Russian oligarchs. Now he has been passed to the sidelines serving his sentence in a Siberian prison camp.

The winnersAmong the winners of Russia's business oligarchs,

Roman Abramovich must be counted as the one who got away scots free. A disciple of Boris Berezovsky, Abramovich benefitted from his patronage in making his way to the top of Russian business. As

the Kremlin moved in on Berezovsky in 1999, Abramovich took over Sibneft - one of Russia's largest oil companies - from his patron along with Russia's largest television network. He then went on to expand his nascent business empire by going into aluminium production by forming Russian Aluminium - the world's second largest aluminium producer. He also went into politics, representing the impoverished Chukotka region of the Russian far east, first as Duma deputy and then as governor, making development of the region his pet project. In 2005, Abramovich sold off 72% of his shares in Sibneft to Gazprom - the Russian state energy company. He has also apparently been able to remain good relations with the Kremlin - both the Yeltsin and Putin administrations. Abramovich has, however, increasingly transferred his assets abroad, buying and investing in western business, most notably the purchase of the English soccer team Chelsea. Today, he spends most of his time in Britain, only occasionally visiting Chukotka, where he remains governor. In March this year, Abramovich was listed by Forbes Magazine as Russia's richest man and the 11th richest in the world.

Vladimir Potanin is the golden boy of the post-soviet establishment. The son of a Ministry of Foreign Trade official, Potanin attended the prestigious Foreign Ministry institute, the MGIMO, before going into business. He started out with trading in

nonferrous metals with his Interros company in 1991, to be followed by two banks - Oneximbank and MFK. Being an architect of the loans for shares program, he benefitted greatly from being able to buy Russian companies much beneath market value. In 1996, Potanin was one the "Big Seven" who assured Yeltsin's reelection. As a token of appreciation, he was then appointed first deputy prime minister by Yeltsin. The August 1998 economic crisis took a heavy toll on Potanin's business empire, but he succeeded in securing crucial assets. His financial conglomerate holds major assets in Russian business such as Norilsk Nickel - the world's largest platinum and paladium producer - as well as media holdings such as Izvestiya and Komsomolskaya Pravda.

As many other successful Russian businessmen,

Mikhail Fridman has kept a low profile throughout his career. Starting out with a plethora of various businesses in the late 1980s, he subsequently

managed to finance the establishment of AlfaBank - now one of Russia's biggest banks. He then went into the lucrative oil business and acquired Tyumen Oil. Cooperating with British Petroleum, Tyumen Oil was transformed into TNK-BP, today the world's tenth largest private oil and gas company. Also Fridman belonged to the "Big Seven" endorsing Yeltsin in 1996. The pinnacle of his business empire is the AlfaGroup holding company.

Oleg Deripaska is one of Russia's youngest billionaires (only Abramovich is younger). As so many others, he

started out with trading in metals. Together with Abramovich, he formed the Russian Aluminium (RusAl) - the world's second largest aluminium producer - in 2000, and now owns 75% of company shares. He has also major interests in power and car industries and he also owns Russia's largest insurance company. Although Deripaska has been careful to keep off the political arena, he is considered one of president Putin's major business allies. Along with his business partner - Abramovich - Deripaska is by some currently considered Russia's richest man.

Born in Baku,

Vagit Alekperov was fostered into the oil business, landing his first job in the sector at 18 years' age. By his

growing expertise, Alekperov in 1991 became first deputy minister of fuel and energy and then acting minister. His main political accomplishment was bringing Russia's three biggest oil companies together to form LukOil. Not surprisingly, Deripaska then became president of Lukoil, a position he has retained ever since. Today, Lukoil is one of the world's mightiest oil companies with energy reserves only equalled by Exxon. He is considered Russia's tenth richest and the 38th worldwide.

From managed democracy to managed oligarchy?Russia during the 1990s has often been compared to the United States during the early 20th century, when Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan and other business tycoons succeeded in forming next to total monopolies in various areas of business. Thus, the Wild West of this era should be equalled to the Wild East of Russia during its first post-soviet decade. Those who seek similarities may today also compare US President Woodrow Wilson's measures to bring down Standard Oil and other monopolistic companies. Thus, today Putin would allegedly be trying to regulate the market after the necessary turmoil of the liberalisation of the 1990s. The Russian state would consequently be trying to regain its position as a macroecnomic arbitrator in order to regulate the market and set the rules of the game.

However, this argument falls flat as the Putin administration displays such a blatant disregard of basic property rights - the very nucleus of a working market economy. That the oligarchs may have done the same in the early 1990s is no excuse for a state to follow such conduct. Moreover, one may argue that one oligarchy today is replaced by another, while the spoils of state action against the oligarchs partly end up in the hands of Putin's entourage, thus effectively redistributing assets from private to private hands instead of to government control. Consequently, Putin's people enrich themselves by forcing parts of Russian business into their own hands. Of course, such behaviour is but a parallel to Putin's political agenda, gaining control over all relevant areas of society. Seeing similarities between Russia of the 1990s and the US of the 1910s becomes laughable if turning to president Wilson's credo of "making the world safe for democracy." It is quite apparent that Putin neither makes Russia safe for democracy nor makes Russia safe for market economy.

Yesterday, deputy head of the Russian Central Bank, Andrei Kozlov, died from gunhot wounds protracted when shot down by armed assailants in central Moscow Wednesday evening. Kozlov is the highest ranking official murdered during president Putin's reign and his assassination now sparks indignation and raises doubts about Russia's fight against organised crime.

Yesterday, deputy head of the Russian Central Bank, Andrei Kozlov, died from gunhot wounds protracted when shot down by armed assailants in central Moscow Wednesday evening. Kozlov is the highest ranking official murdered during president Putin's reign and his assassination now sparks indignation and raises doubts about Russia's fight against organised crime.

growing expertise, Alekperov in 1991 became first deputy minister of fuel and energy and then acting minister. His main political accomplishment was bringing Russia's three biggest oil companies together to form LukOil. Not surprisingly, Deripaska then became president of Lukoil, a position he has retained ever since. Today, Lukoil is one of the world's mightiest oil companies with energy reserves only equalled by Exxon. He is considered Russia's tenth richest and the 38th worldwide.

growing expertise, Alekperov in 1991 became first deputy minister of fuel and energy and then acting minister. His main political accomplishment was bringing Russia's three biggest oil companies together to form LukOil. Not surprisingly, Deripaska then became president of Lukoil, a position he has retained ever since. Today, Lukoil is one of the world's mightiest oil companies with energy reserves only equalled by Exxon. He is considered Russia's tenth richest and the 38th worldwide.